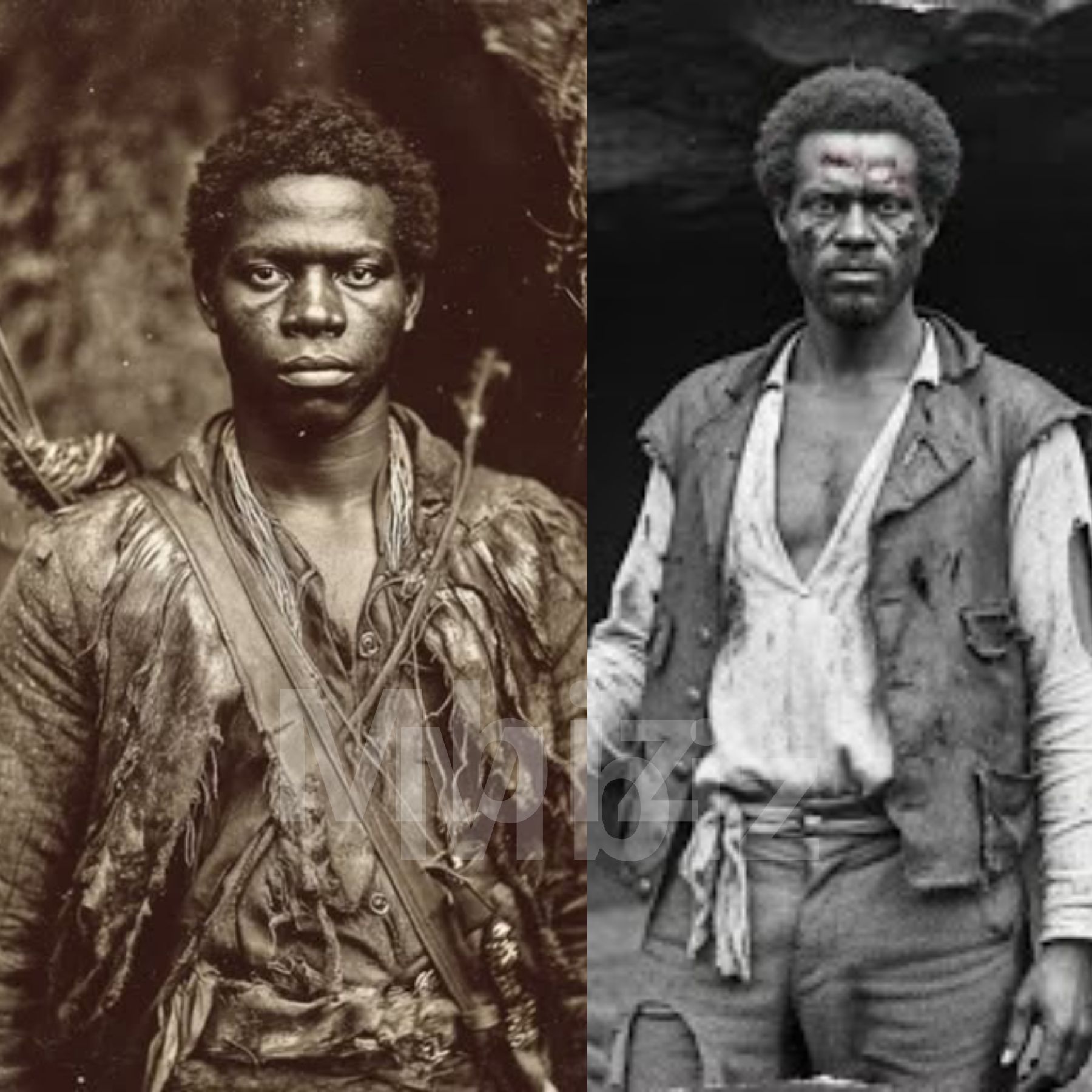

In the autumn of 1843, the valleys and ridges of northern Alabama hid secrets untouched by settlers. The Cumberland Plateau, with its shadowed ravines and dense forests, became both haven and hunting ground for one man—a fugitive whose name would later slip into legend and fear. This is the true and haunting account of Samuel Green, the slave who escaped bondage and became the most feared mountain man in the South.

The Escape

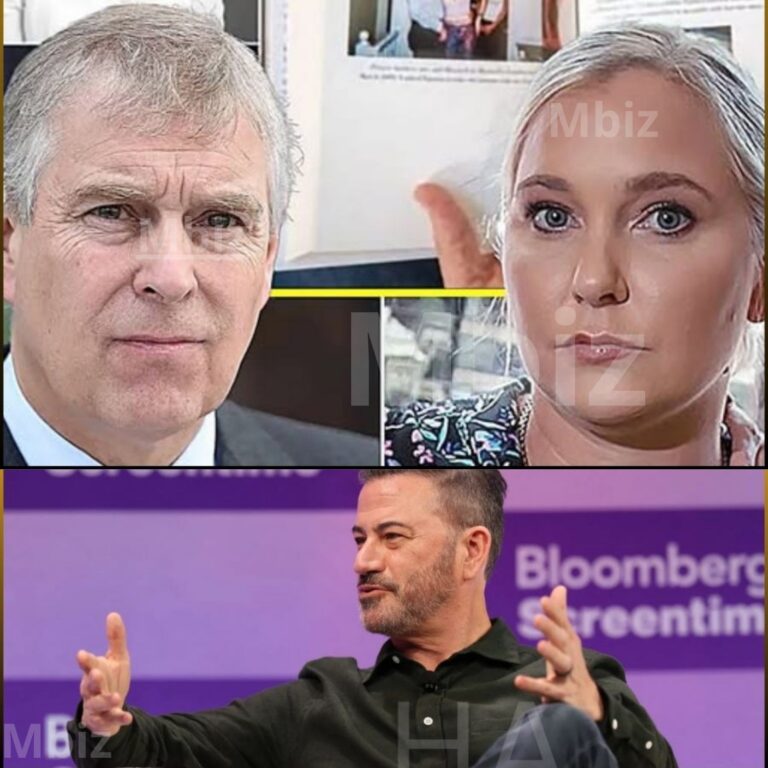

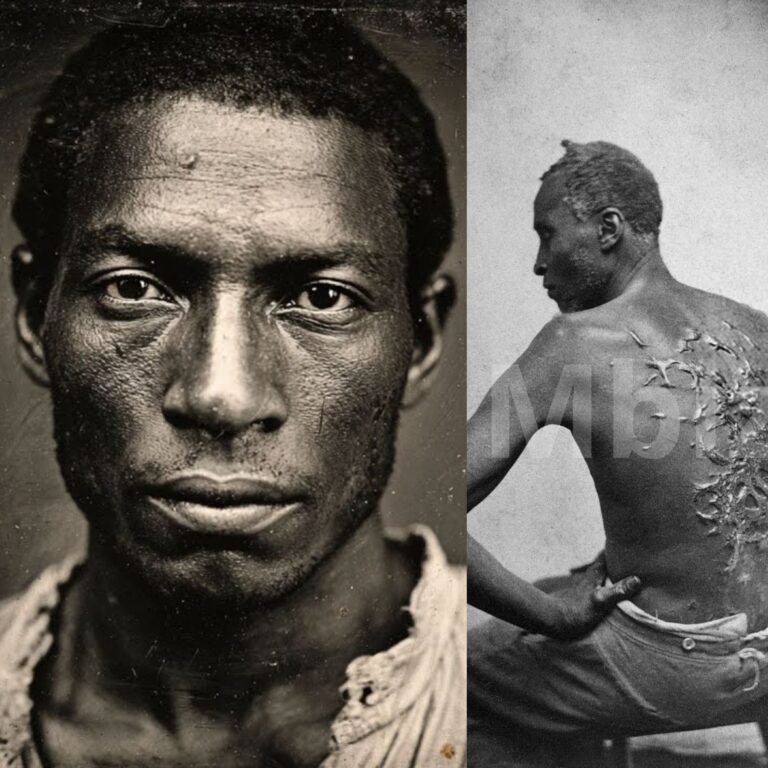

The first written mention of Samuel Green comes from the Johnson Plantation near Huntsville, Alabama. The ledgers describe him simply: “Sam, age 22, field hand—troublesome, twice escaped.” By the autumn of 1843, Green had been whipped, chained, and starved for his earlier attempts at freedom. But this time, his plan was different.

On the stormy night of October 11, 1843, as lightning flashed across the Tennessee Valley, Sam vanished for the third and final time. He took a knife from the smokehouse, a wool blanket, and a fortnight’s worth of dried meat.

But unlike most fugitives who fled north toward the Free States, Samuel Green turned east—into the mountains.

The overseer’s journal noted: “He cannot last long. The mountains will eat him alive.” They were wrong.

The First Sightings

Three months later, a hunter named Elijah Thornton stumbled upon a wild-looking man near what is now Guntersville Lake. The stranger wore animal skins, carried a crude spear, and disappeared into the trees without a sound.

Reports soon followed from trappers and settlers—of a tall Black man with a scar across his cheek, seen moving like a shadow through the forest. At first, these encounters inspired curiosity. Then came the fear.

In April 1844, a hunting party of four men vanished near Scottsboro. Only one, James Carter, was found alive, hiding inside a hollow tree, trembling and half-delirious. His account—recorded by the county magistrate—spoke of “a mountain devil… who struck from the dark, killing swift as lightning.”

Officials dismissed his story. But over the next year, strange thefts began plaguing isolated farms—not valuables, but tools, weapons, and clothing. Homes were entered at night, without broken locks or footprints left behind.

The settlers began calling him The Mountain Devil.

Blood in the Valley

In February 1845, bounty hunter Jeremiah Burke, famed for his brutal efficiency, led a ten-man posse into the mountains to capture the fugitive. They carried rifles, dogs, and a promise of payment from plantation owners terrified that Green’s defiance might inspire others.

Two days later, only one man—Michael Reynolds—emerged alive.

Reynolds, his clothes torn and soaked in blood, told a story no one wanted to believe. Their dogs had gone silent, one by one. Then, “the trees themselves moved.” Men were pulled into the dark without sound or warning. Reynolds said he saw Green standing over the firelight—tall, scarred, and calm—watching him drift downriver.

“He could’ve killed me,” Reynolds whispered, “but he wanted me to tell the story.”

The killings of five white men couldn’t be ignored. Governor Benjamin Fitzpatrick ordered a militia expedition: 40 armed men led by Captain William Holt, with orders to bring Green in—dead or alive.

For three weeks they scoured the ridges, finding empty camps, warm ashes, and carved warnings:

“You hunt a man who learned to hunt from watching you.”

When they finally found Green’s main camp, deep inside a limestone hollow, what they saw defied expectation.

The encampment was part cave, part fortress—fortified with wooden walls, traps, and a thatched roof. Inside were weapons, stolen tools, and the belongings of missing men. Most chilling of all was a journal, written in Green’s own hand.

“I Am What They Created”

The journal’s contents stunned historians when it was rediscovered a century later. Green wrote with anger, but also clarity:

“They made me property, so I became what they feared most. In these mountains I am free—demon of their own making.”

He spoke of the Johnson plantation, of beatings and broken promises, of two brothers in bondage who escaped to join him. He described watching the stars from the ridges and learning the language of the forest—the wind through pines, the sound of men before they speak.

The militia, realizing Green was no savage but an intelligent adversary, withdrew after losing men to ambushes and traps.

But Samuel Green’s story was far from over.

The Master’s Death

On January 7, 1846, William Johnson—the man who once claimed ownership over Green—was found dead in his locked study. A single handmade arrow pierced his chest. On the desk lay a note written in neat cursive:

“Justice comes even to the mighty. Remember Samuel Green.”

The region erupted in panic. Another militia of sixty men was assembled. This time, they weren’t instructed to capture him. Only to kill.

Two weeks later, seventeen soldiers were dead. The rest fled. Their commander wrote: “We do not fight a man, but a ghost. He moves with the storm. The men will not go back.”

The legend of The Mountain Devil was sealed.

From Man to Myth

By 1847, sightings grew rarer. Then one final report came from a surveying team near the Alabama–Georgia border. The men described a tall, scarred man who approached peacefully, unarmed.

“I am Samuel Green,” he told them. “These mountains remember me. Now I go to find what freedom truly means.”

He walked away, and was never seen again.

The Whispered Legacy

Decades later, enslaved people across northern Alabama still spoke of Mountain Samuel—the shadow who avenged cruelty.

One elderly woman, interviewed in 1937, said her mother told her:

“If the master whipped a man too hard, the mountain devil would come. He’d know. And he’d set it right.”

Even white overseers grew cautious. Plantation letters from the 1840s warned against excessive punishment:

“We must tread carefully. There is a devil in these hills who judges cruelty.”

For those trapped in bondage, Green’s story became a secret gospel—proof that even the enslaved could strike back.

The Letter from Pennsylvania

In 1898, historians found a letter in the archives of the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society. Dated May 1848, it spoke of “a remarkable man just arrived from the southern wilderness,” who called himself Samuel and claimed to have lived as a wild man in Alabama’s mountains.

He carried a leather-bound journal, the letter said, and sought passage to Canada.

If it was truly him, Samuel Green had survived four years in the wilderness, exacted vengeance on his master, and escaped the South forever.

The Man Who Became the Mountain

For nearly a century, Green’s name drifted between history and folklore. Some called him a demon. Others, a savior.

In 1997, archaeologists from the University of Alabama uncovered a hidden structure in the Plateau cliffs—a small cabin built into stone, with modified weapons, tools, and a metal button from the Johnson plantation era. Carbon dating placed it around the 1840s.

Dr. Margaret Wilkinson, who led the excavation, said:

“It wasn’t just survival. It was sovereignty. Whoever built this wasn’t hiding—he was ruling his world.”

Fear and Freedom

For white settlers, Samuel Green was a nightmare—proof that the enslaved could become predators. For enslaved people, he was something else entirely: a symbol of defiance, justice, and self-liberation.

During the Civil War, Union officers recorded stories from freedmen about “a black spirit of the mountains who punished cruel masters.” Even decades after his disappearance, his legend served as protection.

One former overseer wrote bitterly in his memoir:

“Every whip cracked softer in those years. Men feared the eyes in the hills.”

The Return of the Legend

In 2009, the Scottsboro Heritage Museum unveiled a small exhibit titled “The Mountain Devil: Myth and Man.” It featured Green’s journal fragments, maps of his suspected territory, and a single replica arrow.

At the dedication, historian Dr. Terrence Watson summarized Green’s legacy:

“Samuel Green destroyed the illusion of white invincibility. Every patrol that hesitated, every overseer who showed restraint, was a victory he earned from the shadows.”

Today, hikers who wander the fog-covered ridges of the Cumberland Plateau still tell stories. Some claim that at dusk, when the wind moves through the pines, you can hear faint footsteps—or see a figure standing just beyond the tree line.

A reminder that once, in those mountains, a man who was born property became legend.

Epilogue

The last words in Samuel Green’s journal—now preserved in the Alabama archives—capture the defiant spirit that turned him from fugitive to phantom:

“They made me invisible, but I learned to see in darkness.

They made me property, but the mountains made me a man.

I was born a slave.

I will die free.”

And somewhere, perhaps beneath those ancient ridges, his echo remains—Samuel Green, the man who taught the South that even the hunted can become the hunter.